Social vulnerability occurs when the disadvantage conveyed by poor social conditions determines the degree to which one’s life and livelihood are at risk from a particular and identifiable event in health, nature, or society. A common way to estimate social vulnerability is through an index aggregating social factors. This scoping review broadly aimed to map the literature on social vulnerability indices. Our main objectives were to characterize social vulnerability indices, understand the composition of social vulnerability indices, and describe how these indices are utilized in the literature.

A scoping review was conducted in six electronic databases to identify original research, published in English, French, Dutch, Spanish or Portuguese, and which addressed the development or use of a social vulnerability index (SVI). Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened and assessed for eligibility. Data were extracted on the indices and simple descriptive statistics and counts were used to produce a narrative summary.

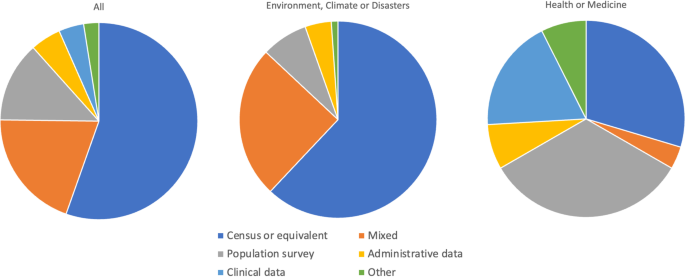

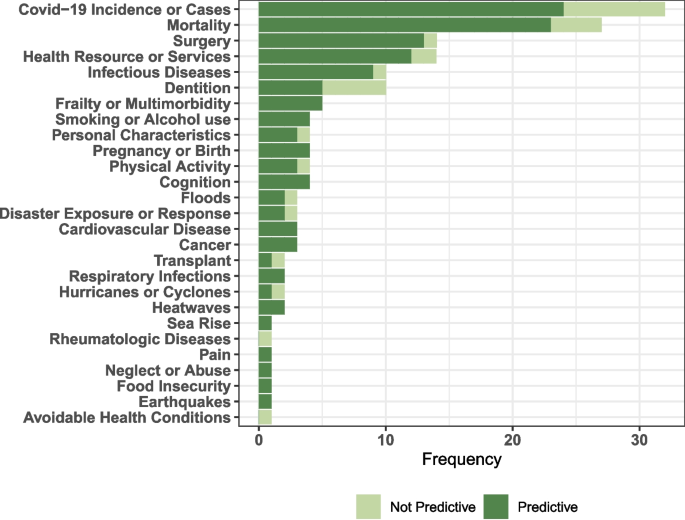

In total, 292 studies were included, of which 126 studies came from environmental, climate change or disaster planning fields of study and 156 studies were from the fields of health or medicine. The mean number of items per index was 19 (SD 10.5) and the most common source of data was from censuses. There were 122 distinct items in the composition of these indices, categorized into 29 domains. The top three domains included in the SVIs were: at risk populations (e.g., % older adults, children or dependents), education, and socioeconomic status. SVIs were used to predict outcomes in 47.9% of studies, and rate of Covid-19 infection or mortality was the most common outcome measured.

We provide an overview of SVIs in the literature up to December 2021, providing a novel summary of commonly used variables for social vulnerability indices. We also demonstrate that SVIs are commonly used in several fields of research, especially since 2010. Whether in the field of disaster planning, environmental science or health sciences, the SVIs are composed of similar items and domains. SVIs can be used to predict diverse outcomes, with implications for future use as tools in interdisciplinary collaborations.

There has been increased interest in understanding social vulnerability within medical sciences and medical practice. Social vulnerability in medicine is bi-directional; it contributes to the factors which increase risk of adverse health conditions and has practical implications for arranging supports after an adverse health event. Social vulnerability provides a way to understand how the broader conditions in which people are born, live, work and age can worsen an unfortunate event (e.g., a health crisis) into a veritable disaster [1, 2]. Reducing social vulnerability through modification of social conditions opens intervention opportunities to prevent or reduce suffering after a health event.

A better understanding of social vulnerability can be elucidated by examining interdisciplinary social vulnerability research. Social vulnerability has roots in a rich and evolving literature base involving various natural, health and social disciplines. For example, a review of social vulnerability in climate change helps make sense of the complexity of this concept [3]. Assessing social vulnerability enables the separation of the biophysical dimension from the human and social dimension of susceptibility to climate events [3]. Moreover, social vulnerability as a concept reflects both the capacity of a system to respond from an impact as well as an intrinsic lack of capability of individuals to cope with external stressors [3]. Another common working definition in disaster planning refers to the “characteristics of a person or group in terms of their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” [4], often compounded by the inability of the external system to respond. Similarly, adverse events, whether disaster or health-related, tend to expose, and make it possible to capture, the pre-existing social inadequacies that make individuals or communities disproportionately vulnerable. When we apply this to social vulnerability within medicine, it can be viewed as describing the non-health dimensions that keeps individuals incapacitated longer than expected (e.g., in hospital unable to return home) because of social circumstances close to the individual (e.g., marital status) but also because of social support systems that fail to respond or perpetuate vulnerability (e.g., lack of affordable housing for people with disabilities).

Regardless of field, social vulnerability research strives to understand the social environment not just as a descriptor but as a predictor of vulnerability relative to changes in the environment, social circumstances, disasters, or health status [1, 5,6,7]. To this end, estimating and quantifying social vulnerability is necessary. A common way to estimate social vulnerability is through an index aggregating social indicators. This approach has several benefits, including the opportunity to include variables from different categories of social factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, social engagement, social capital) instead of a one-at-a-time approach [1]. An index does not arbitrarily separate related factors into distinct categories for separate analysis. Moreover, it allows for gradations in social vulnerability (instead of binary or ordinal social variables) and for scaling to account for different units of analysis [1, 8]. In practical terms, an index overcomes the following dilemma. Two households with an average income below the poverty line may be classified as vulnerable in a study examining household income. Suppose one household comprises a recently graduated, working-age, married couple well integrated into the community with strong social ties, and the other is an older adult living off government assistance with no friends or family who could help in a time of need. Thus, there are two distinct tiers of social vulnerability not captured by examining household income alone.

One problem with an index approach is deciding which social factors to include in a social vulnerability index. Items to be included can be limitless or highly context dependent. Cutter and colleagues [9] have previously noted that there are no accepted sets of variables for vulnerability to climate change, but there is general consensus on using age, gender, race and socio-economic status; while necessary, these four factors are insufficient to give the full picture of social vulnerability. Furthermore, a worthwhile endeavour may be to create a social vulnerability index relevant to medical and health contexts, yet there have been only a few social vulnerability indices published specific to medicine [10,11,12]. Looking at the social factors composing these few indices relevant to medicine does not provide breath of social conditions if we understand social vulnerability to be an interdisciplinary concept encompassing both the individual’s and system’s inability to cope. Expanding this pool of commonly used variables to include in a social vulnerability index would provide additional benefit for future indices, and for indices relevant to medicine.

This scoping review broadly maps the literature on social vulnerability indices. Our three main objectives were: (1) to characterize social vulnerability indices, (2) to understand the composition of social vulnerability indices, and (3) to describe how these indices are utilized in the literature.

This scoping review uses the Arksey and O’Malley framework refined by Levac, Colquohoun, and O’Brien [13, 14]. We also followed the PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews (see Additional file 1).

An electronic search was carried out to locate publications in the following databases: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Embase, Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL), Public Affairs Index, and Environment Complete from inception to December 1, 2021. No other search terms were included given the specificity of the term “social vulnerability index.mp” or “social vulnerability indic*.mp”. We used the web-based platform Covidence® as the primary screening tool.

The following inclusion criteria were adopted: (i) original research; (ii) published in English, French, Dutch, Spanish or Portuguese (languages spoken or read by the research team or affiliates); (iii) and which addressed the development or use of a social vulnerability index (hereafter called ‘SVI’). We excluded studies: (i) where a larger index incorporated an SVI and that larger index no longer focused on social vulnerability; (ii) analyzing social factors individually and not the index itself; and (iii) including non-human participants.

Titles and abstracts of search records were screened by two team members independently. We also worked independently to review the full texts of records deemed potentially eligible after the title and abstract screening phase, excluding publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were decided by consensus or judication by a third author.

We extracted data using a piloted data collection form including general study information (reference, year, location), study objective, population, the field of study (we decided a priori to categorize this by: (1) environment, climate or disaster, (2) health or medicine, or (3) other), and composition of the social vulnerability index (items, calculations, scale of measurement, underlying theory). Here, SVI items were the individual questions or statistics (e.g., proportion of institutionalized individuals in a region) comprised in an index. Each SVI constituted one observation in the charting of the index composition and multiple studies using the same constructed SVI were linked. We hand searched reference lists and reported on the earliest publication of the original SVI. Complete information was extracted for studies describing an original SVI (defined by the review authors as the first published study that describes an SVI with least five different items/domains from a previous SVI and a 25% change in a previous SVI’s items). To answer objective 2 regarding the composition of the indices, we established this criterion to avoid overrepresentation of items/domains from frequently replicated SVIs (which may have been reproduced in other datasets with only a few items or domains added or dropped). For studies using a previously described index (hereafter called ‘replications’), we extracted only general information, population unit, field of study, study objectives and outcomes when the SVI was included in predictive modelling. We also emailed authors to get additional information when necessary.

Simple descriptive statistics and counts synthesized the extracted data. We also documented when the SVI was used in an environmental, disaster management, or climate change-related field and when the SVI was used in a health or medicine-related field. To better understand the composition of the SVIs, we tallied each item and re-aggregated the items into domains. The domains were derived from a thematic aggregation of the items in an iterative and consensus-based approach. Finally, we report on a subset of studies that used an SVI to predict outcomes. If the purpose of the SVI was predictive, we recorded and counted the outcomes.

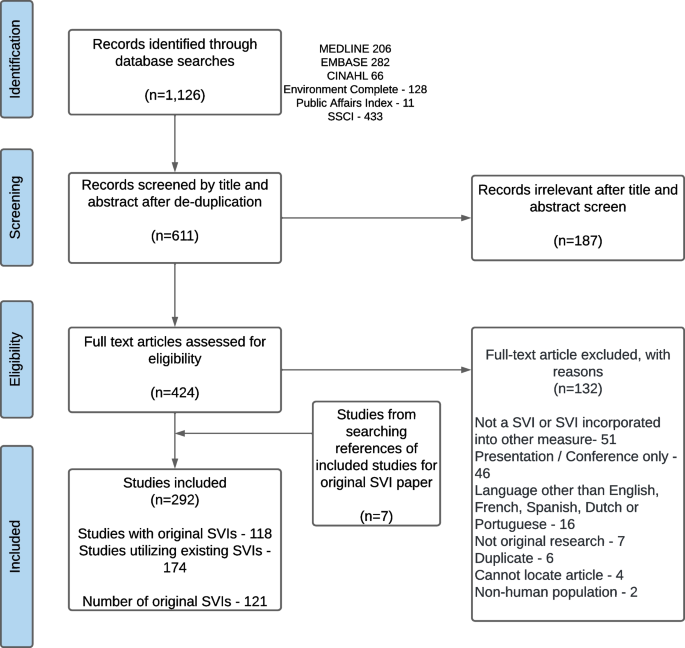

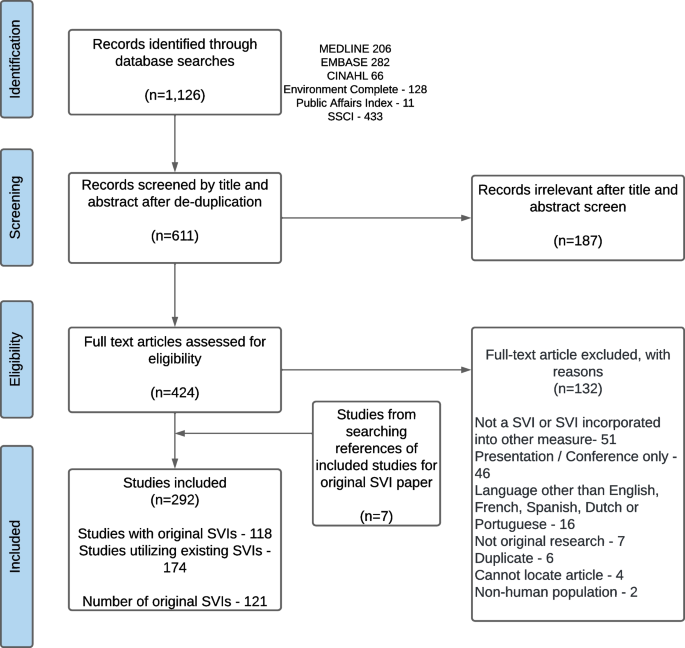

The search retrieved 1,126 records of which 515 were duplicates. After screening of titles and abstracts, 187 records were excluded, and 424 full text articles were obtained (see Fig. 1). There are 292 studies included, of which 118 studies examined original SVIs and 174 studies examined replicated SVIs. Of the 118 studies which examined original SVIs, three of the studies examined two SVIs each, therefore the number of original SVIs is 121 (Additional file 2 provides complete references divided into original and replicated SVI studies).

The study characteristics are summarized in Table 1 with full details of each SVI available in Additional files 3 and 4. Overall, 53.4% of studies (156/292) reported on the SVI in relation to the fields of health or medicine. Among original SVIs, most were developed for an environmental or disaster planning field (90/118). Of the 292 included studies, 42.8% were conducted in the United States of America (USA) followed by Brazil (18.8%), and 49.7% of studies were conducted after 2019.

In total, there were 122 distinct items identified. We categorized these items into 29 domains shown in Table 2. The top three domains included in the SVIs were: at risk populations, education and micro level socioeconomic status. Of the 121 original SVIs, 76.0% included an item in the domain of at-risk populations. More (87.0%) environment, climate or disaster SVIs included this domain than health or medicine SVIs (40.7%). Of the 92 SVIs which included an item within the domain of at-risk populations, an item about older adult populations (terms senior or elderly were often used) was most common in 84% of SVIs. In the health or medicine SVIs, the most common item for at risk populations was regarding dependent populations.

In this scoping review, we provide an overview of SVIs in the literature with a focus on mapping out the composition of these indices and how they are used to predict outcomes. While there are few systematic or scoping reviews on indices of social vulnerability specifically, there are two grey literature narrative reviews on social vulnerability assessment tools by the United Nations Development Programme for climate change [27], and the US Corps of Engineers’ Institute for Water Resources [28]. These reviews have previously hypothesized that, despite heterogeneity in the indicators used, the methods for calculating SVIs are relatively similar in most situations. Our findings support that hypothesis and add a broadened scope by including SVIs in the fields of health and medicine.

We also mapped items and domains used in the composition of SVIs as one way of answering an often-debated question: which social factors should be included in an index to represent social conditions? Despite differing fields, purposes and applications of the 121 original SVIs included in our review, we found seven domains of social factors that were used in the composition of over half of the SVIs: at risk populations, education, micro (i.e., individual, family or household) level markers of socioeconomic status, household composition, employment, housing, and population health statistics. In these domains, there are items from both the individual level, the household level and population level. Individuals’ vulnerabilities cannot be separated from their systemically disadvantaged communities and our finding that one in five SVIs used mixed data sources suggest that future SVIs may be strengthened if composed of social factors reflective of vulnerabilities at the individual, family, neighbourhood and community levels.

Not mentioned in the domains above is gender or sex, despite previous consensus that this item should be included in a SVI [9]. Since it is well documented that gender and sex differences (biologically and socially) contribute to different experiences and outcomes in health [29] and disasters [30], we were surprised that less than 50% of SVIs included gender or sex. This may reflect a choice of the researchers because most items for SVIs came from census data or population-based surveys, so variables on gender or sex demographics are not readily available. There were no variables reflective of sexuality. The exclusion of sexuality as a determinant of social vulnerability can be problematic as it makes invisible the challenges faced by sexual minorities (e.g., perpetuating discrimination), masks disparities (e.g., in access to housing, healthcare access or social services) and fails to recognize the intersectionality whereby sexual minorities are often part of multiple vulnerable groups. Other commonly included SVI items that would likely be gendered depending on the context, include educational and occupational opportunities, and also marital status and living situation. We were surprised that items like single parent or female-headed household were less prevalent in the health and medicine SVIs (see Additional file 5) and overall, we had expected consideration of sex and gender-related items to be more common. While it is possible that gender or sex stratified analyses are being conducted instead of including specific items in the index, our findings suggest that many SVIs may be missing an important determinant of vulnerability. Researchers need to carefully consider how to construct their indices and choose data sources with information collected on sex and gender. The most frequent variable was a dichotomized proportion of sex or gender, reflecting previous literature describing how the dominant discourse in disaster management on sex and gender is binary, and does not account for gender minorities [30].

This paper adds to the literature in two key ways. First, our findings confirm that interest in measuring social vulnerability is increasing, especially in the health and medicine fields (Table 1). This growing trend seems to have been linked to researchers trying to understand the social and economic factors contributing to the differential impacts of the pandemic across various populations. The interest may also be tied to the rising importance of interdisciplinary research, the growing recognition of climate change’s impact on social and health inequities and the advances in available data in which to conduct social vulnerability research. We also demonstrate that when SVIs are used to measure an outcome, the outcome was overwhelming in the health and medicine fields, and the SVI was predictive. However, the SVIs in health or medicine related fields were more often replicates than original SVIs, suggesting health and medicine studies are employing SVIs developed for other fields of literature (e.g., SVI by the CDC/ASTAR). Social vulnerability is often context dependent and having more original indices with community specific data may be a better tool for measuring social vulnerability related to health. Second, we provide a scaffold for future researchers looking to create these original SVIs. There are many ways to choose social factors in an index from theory driven to data availability to community consultations; however there is no gold standard. Here, we provide another way of making this determination by summarizing what past SVIs have used, from most common to highly context specific (Additional file 5). A strength of our approach is that it includes items and domains that take into consideration individual capacity to recover from the impact of a hazard as well as the inability of the system to respond. Our approach also encompasses global items from literature in five different languages and incorporates items from several fields of research in keeping with the interdisciplinary nature of social vulnerability.

Whether we are evaluating risks from an adverse health event or disaster event, the social production of vulnerability should be given the same degree of importance dedicated to understanding and reducing the medical or environmental risk. Our findings show the social vulnerability index predicts many outcomes from mortality to frailty to disaster response. We also see that SVIs used globally. Unlike other measures which were developed and are more applicable to high income countries (e.g., the SVI by the CDC/ASTAR), the SVI appears adaptable and relevant to different contexts whereby original SVIs are emerging from all continents (except Antarctica). It also appears that one recent and frequent application of SVIs is for Covid-19. SVIs have been used as a research tool but also as a pragmatic policy tool to identify and support vulnerable communities through resource allocation [31]. Certain tools (i.e., the SVI by the CDC/ASTAR) that are free, easily accessible, and have complete data are most replicated and may facilitate researchers and policymakers taking an interest in social vulnerability [31]. If authors are creating SVIs, they should strive to use publicly available and free data and replicable with a simple methodology as this will reduce barriers to use of SVIs in broader research.

There remains many complexities and uncertainties for researchers hoping to employ SVIs, and our study has limitations which should inform interpretation of our findings. The choice to categorize indices into three broad categories (i.e., environment, climate or disaster, health or medicine, and other) may have resulted in loss of information or loss of opportunity to detect differences within fields. By excluding papers where social vulnerability indices were combined with other measures (i.e., weather indices), this review does miss out on other potential applications of the SVI. Furthermore, the search was very specific due to feasibility constraints of screening hundreds of full-text papers. There are undoubtedly many indices with the same underlying principle that are perhaps not called an SVI. Indices that may be made on social resilience factors were not part of the search, yet is one area of future exploration as it is unclear if an index of social strengths (i.e., a strengths-based resilience index) would yield comparable results to a social vulnerability index. Another consideration is that this review did not explicitly collect data on the methods authors used to determine inclusion of items (e.g., theory driven, data availability, factor analysis, community consultation, etc.). Nonetheless, to balance feasibility of the search, we still provide a review with a significant sample size with the inclusion of several languages.

There are several areas of future research on SVIs. First, validating and comparing different SVIs to understand their strengths and weaknesses and to identify the most appropriate indices for specific purposes is needed. Second, understanding trends in social vulnerability over time and determining what this means for building an index to represent social conditions at different stages of life is also needed. Finally, future studies should build on the recent pragmatic uses of SVIs during the Covid-19 pandemic, which used SVIs to plan and evaluate effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce social vulnerability.

Identification of social vulnerability presents an opportunity to intervene to improve the lives of individuals and communities following an adverse health or disaster event. To identify social vulnerability, social vulnerability indices are commonly used. The social vulnerability indices presented here brings together multiple fields of literature and demonstrates growing interest in using these indices in health and medical literature. We also found that SVIs predicted Covid-19 cases, mortality, surgical access or outcomes and healthcare access or resources, among other outcomes. Since we predict the use of SVIs will continue to increase, we also provide a summary of domains and items common across SVIs in the literature, which provides an alternate method of constructing SVIs in the future. The social vulnerability indices presented here brings together literature from multiple fields of literature; whether in the field of disaster planning, environmental science or health care, the SVIs are composed of similar items reflecting interdisciplinary ways of thinking.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MKA and JCM are part of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) Team 14, which investigates how multi-morbidity, frailty and social context modify risk of dementia and patterns of disease expression. The CCNA receives funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CNA-137794) and partner organizations (www.ccna-ccnv.ca). The authors would also like to thank members of the Geriatric Medicine Research team who helped translate several papers.